The ingredients of Italian main dishes

The original idea

Food is a favourite theme for my data cards. I originally wanted to compare Italian and Spanish typical food, with the hypothesis that the second is much more varied in ingredients and styles, the idea being that Spain has been a major empire so it must have imported flavours and methods from many parts of the world, building a rich culinary repertoire. This is certainly the feel I get from what I know of Spanish food, totally based on experience and likely confirmation bias. I was looking for data that would prove or disprove this but I didn’t have much luck as I needed reliable, vast and respectable sources that also happened to be accessible in machine-readable format.

My first goal was building a list of ingredients with their prevalence, for both Italian and Spanish food. I initially thought I’d query the Internet Archive for books and magazines that could represent the two cuisines well. Usually you can find OCR’d text - from there it would have been a case of parsing the texts to isolate and count all ingredients. I thought I’d do some googling and ChatGPT-asking to first choose a list of reputable sources to look for, as I needed books and magazines focussed on national food, not stuff that could contain fusion/foreign influence. This is a slippery slope per se because what is “national” food anyway? Where does “tradition” end to branch into “global” or “modern”? Where would one put the divide as to what’s genuinely representative of a national cuisine and what’s not, and why? These are deep questions that transcend the scope of my little exploration and also, that would require a deep dive into the sociology and anthropology of food.

The attempt didn’t work anyway, because the Internet Archive doesn’t have - in a digitised form - any of the books or magazines that my googling and ChatGPT’ing suggested, and that the human that is me then vetted to gauge as to whether they could be good sources. I found a bunch of editions of an Italian famous magazine, quite fit for purpose, but no Spanish equivalent. I found good books but not digitised/available.

And so, this is how I decided to focus solely on Italian food instead, scaling down to a simpler project. I know good sources of Italian food material.

The data

I decided to then lean on an institution of Italian recipes, the website Giallo Zafferano (note: it exists as an English version too). It is so authoritative that it has a Wikipedia page. The choice was also motivated by open source code that would allow me to quickly scrape all recipes, so I didn’t have to do it myself - this one1.

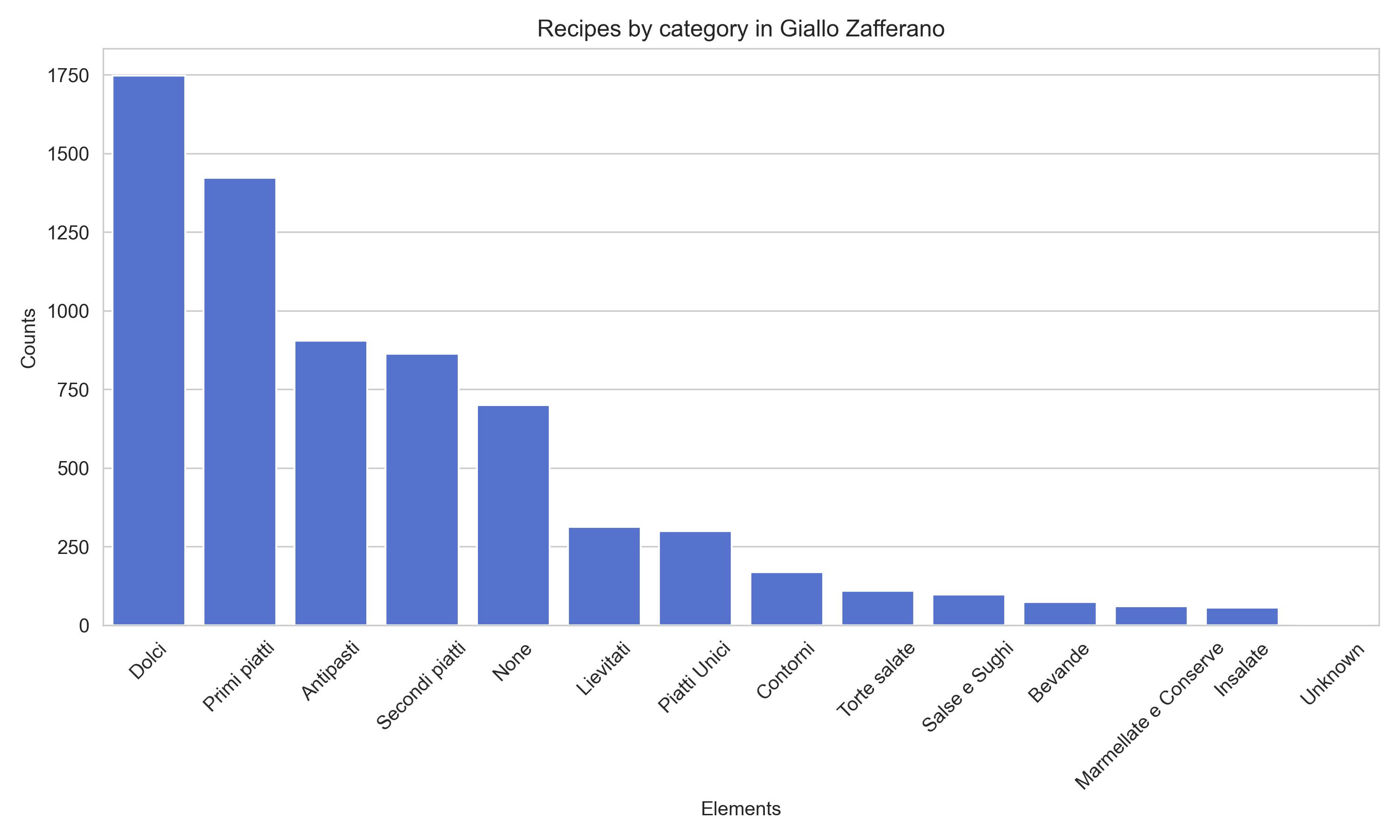

At the time of running the scraping (29th March 2024) I ended up with 6819 recipes; each recipe comes with ingredients (what I care about), a category and of course the procedure. The total of ingredients overall is 1763 - counted as unique strings, so different spellings or writings of the same thing (possible!) will contribute to this count.

Categories

So, a typical (?) Italian meal is made of a:

- Primo - carbs with sauce, veggies or meat/fish: this is your pasta dish, but to smaller extents there’s dishes with rice or other grains. Soups and similia fall in this category too;

- Secondo - meat or fish;

- Contorno (side dish) - goes with the secondo: think veggies;

- Fruit/Dolce - either or both, dolce is the dessert. Usually people have fruit at home and a dessert only when eating out or on Sundays and special occasions, but of course, it depends.

Now, what is “typical” is up for discussion of course. I follow a bunch of great creators on Instagram and what they cook, reinterpret and create is far from this “typical” (for instance, I think it’s become way more popular to create bowls or otherwise “complete meal” dishes), but let’s stick to this for the sake of argument, and also because that’s how GF is organised.

Desserts trump primi in GF, this was to me a bit of a surprise.

Primi piatti, with ChatGPT

I’ve decided to focus on primi piatti (first courses), mostly for the sake of reducing the scope of work but also because I feel that they’re really the core of where you find genuinely Italian stuff.

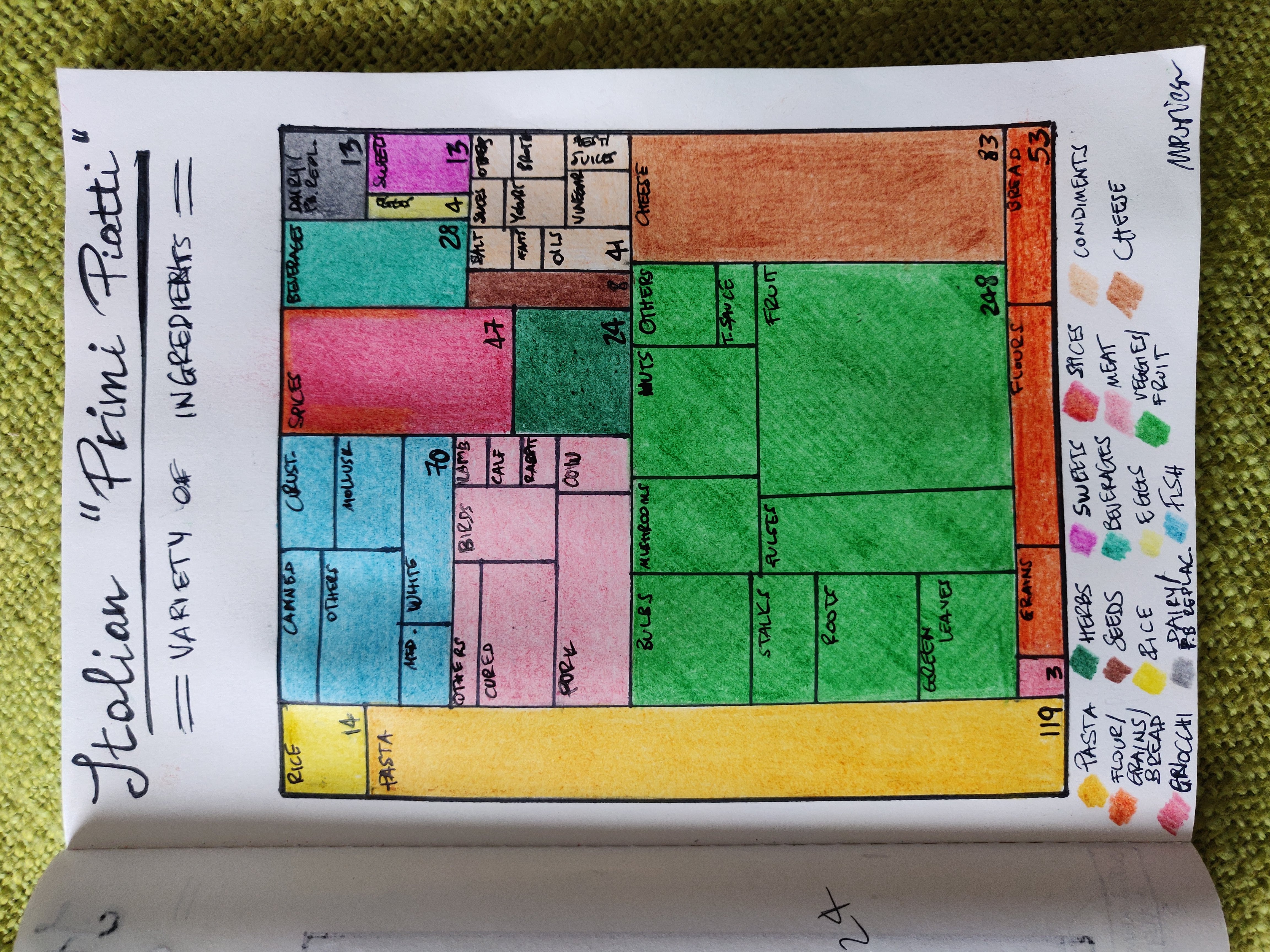

This is where the fun began - I started looking at the ingredients for “Primi Piatti”, expecting naturally that pasta would take the lion’s share. Of course, pasta, like us humans, appears in many formats and shapes, so I knew I had to do some words-grouping. The total of unique ingredients for first courses is 857.

My lovely aid ChatGPT (with GPT 3.5) was instrumental in achieving the grouping of this long list into subcategories: I’ve gone down an iterative process of repeatedly asking it to isolate all ingredients belonging to a group from the list, and it did pretty well. For example, one group was “pasta” and a prompt asking for all pasta types in the list produced a fairly long list of pasta shapes indeed - really helpful. The groups to ask for were decided by me; I’ve worked off of common sense and my knowledge of the food of my roots, but I’ve also iteratively looked at counts of what was popping up most frequently amongst recipes: for example, things like oil and salt are at the top of the frequency list for obvious reasons and I’ve decide to establish a group for “condiments”. The whole process still took some human refinement, the aforementioned decisions on what groups to ask for in the first place and of course lots of checks: GPT was very helpful but it did sometimes hallucinate either spitting out ingredients not present in my list (this seemed to happen a lot for groups that are scarcely populated, it struggled to find items for them and made many up) or missing ingredients altogether. Note that the ingredients it invented were all very plausible, sometimes plurals of existing ingredients (e.g. “cipolle” for “cipolla”), so the only way was really to check that for every list it gave me back all elements did exist in the original. Another thing ChatGPT did, but this was occasional, was misplacing items in a group.

Working in tandem by checking frequencies dynamically (while I was grouping), doing the checks and iterating made it so that at the end I ended up with 16 groups: pasta, rice, flour/other grains/bread (it can be part of a main), gnocchi, meat, fish, cheese, veggies/fruit, herbs, spices, condiments, seeds, beverages (think dishes cooked in wine), eggs, sweet things (occasionally used for primi!), dairy/plant-based replacements.

These 16 groups cover 814 ingredients - from the original 857 I’ve excluded some (about 30) clearly out of the realm of Italian food (many Asian like “Miso” and “Pak Choi”) which are used to present recipes from other places, and yeasts, plus a handful of things I wouldn’t have known how to group and that weren’t important anyway. I have also removed some frankly weird stuff like “panettone” which was used in a “risotto al panettone” recipe.

I should also note that for the items ChatGPT missed in a group, that I could see in my frequency counts, VSCode was very helpful as its automatic (?) parsing of a repo made it super easy to add them in a list (typing two chars gave the whole string quickly).

This dataset of 16 groups and 814 ingredients I’ve obtained this way also had the additional feature that the most complex groups had been separated into subgroups, for instance the meat group has subgrouping by type of animal - this was all courtesy of ChatGPT as I didn’t ask for it specifically.

A few notes about these ingredients:

- There’s a plethora of recipes for things like lasagne or cannelloni, which are technically pasta, but the recipe makes you do the pasta from scratch so the base ingredient is flour - this contributes to the flour/grains/bread group. Similar reasoning applies to gnocchi recipes, most recipes make you do them from scratch.

- the cheese group is all genuinely Italian cheese apart from a handful French ones - I left them in as they’re popular and much used in Italy too.

- “peperoncino”, the vulgar name for what is - I think - Cayenne, has been placed with all its appearing varieties within the “spices” category even though there are dishes with the whole vegetable, but in order to know whether it’s used as a spice only or a base thing you’d have to manually check the recipes, so I’ve taken a call.

- In the pasta category I’ve left those instances of pasta made without wheat (gluten-free versions) or with more than just wheat, like the types added with legumes.

The data card

I’ve decided to use a treemap for this, which is a type of graphic showing the proportion each item occupies in a dataset as part of a big rectangle: each item is itself a rectangle and the fun thing is you can nest treemaps, so you can easily create the sub-treemap for each item - which is exactly what I’ve done here with the subgroups of ingredients. This has been the primary reason why I chose this type of representation, but I also just really like it, I think it conveys information very quickly. I could have hardly used anything else for this two-layer data.

Each rectangle is a group of ingredients and is coloured accordingly - I have tried to use “representative” colours, that is, colours that would easily give you a mental map of each group: for instance, I’ve used green for veggies/fruit, pink for meat and light blue for fish. Some colour choices are admittedly more dubious (like a light brown for cheese), but it was those things that didn’t immediately call for a hue in my mind (and also, I needed to generate enough diversity in colours for you to be able to distinguish things). Every group shows the number of ingredients that belong to it (bottom-right of each rectangle). The treemap-nesting is evident: those groups of ingredients with subgroups (thanks again to ChatGPT who did the heavy-lifting here!) share the colour but are identified by sub-rectangles.

So what do we learn? Of course, the obvious stuff like Italian food is rich in pasta dishes or that there’s a fair use of meat and fish. But also, that vegetables are really common, varied and (my addition) exploited for maximal flavour: you can easily be a vegetarian in Italy (vegan is a bit more difficult due to the love for cheese, but this is all another story).

Notes for improvement

- It has escaped me that “yoghurt” is not listed in the “dairy/plant-based replacements” as it should but is instead part of the “condiments” group. This was ChatGPT’s choice and I’ve apparently not noticed/thought about it, either when checking things or when drawing. The other thing about yoghurt as an ingredient for a main course is that it feels weird for Italian food, so I went to check (after everything was done) which recipes it belonged to and it is a combination of sauces and dressings. It should have been in dairy anyway.

- Sweet things are also dubious: there’s things like chocolate and honey. They are used for genuine main recipes but arguably it’s very niche things.

- Anything else that looks weird to you? Let me know!

Liked this? I have a newsletter if you want to get things like this and more in your inbox. It’s free.