Artificial neurons and logical tables

A post on artificial neurons, which are somewhat the basis of neural networks, themselves the basis of artificial intelligence! The topic is of course long, rich and multi-faceted, but let’s dig into some of the foundational ideas.

The human brain has 100 billion neurons, each neuron connected to 10 thousand other neurons. Sitting on your shoulders is the most complicated object in the known universe.

Michio Kaku, in an interview (2014)

Neurons

Neuron theory

For a long time, scientists believed the human brain was a single, continuous chunk of matter organised in a reticulate with floating small organs that behave in an undifferentiated way. It was Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852-1934), a Spanish medical researcher, to illustrate, literally, that it is instead composed of individual unit cells connected in such a way to form a hierarchical system capable of performing highly specialised tasks.

Ramón y Cajal wasn’t born in a privileged or well-known family and he came from a small village, but his father - a doctor - initiated him to the science and practice of medicine, although this was still the time when surgeons and barbers where one and the same: you went for a haircut to the same place where you went for a wound suture or a tooth removal - indeed the “barber pole” with its white and red colours has its meaning in this. Santiago Ramón y Cajal moved to Zaragoza to study medicine as a young man and then spent his career in several notable cities in Spain, most importantly Madrid and Barcelona. He was also called to serve in the the Ten Years’ War (1868-1878) against Cuban rebels, performing medical duties for the army.

From an early age he displayed an amazing talent for drawing and throughout the years he produced many very-detailed and beautiful illustrations of brain matter which became pivotal to the emergence of what became known as the “neuron theory”. His illustrations are used to this day, and indeed they are beautiful.

Ramón y Cajal perfected Camillo Golgi’s staining method, which allowed for the clear visual isolation of just a subset of the cells in neural matter by virtue of a process known at the time as the “black reaction”, which made just a few cells appear as coloured in black. This way, he could then put what he saw on paper, which allowed him to understand how neural matter really is structured.

His work wasn’t really appreciated from the start, quite the opposite indeed. On top of the fact that it proved to be really hard to dislodge the common conviction within the scientific community that the brain wasn’t made of individual cells, he also suffered from outright discrimination within scientists’ circles (which were very elitist) due to his modest upbringing. It took a while for the neuron theory to be accepted: Golgi himself, in his Nobel lecture (text available here) states “I shall therefore confine myself to saying that, while I admire the brilliancy of the doctrine which is a worthy product of the high intellect of my illustrious Spanish colleague, I cannot agree with him on some points of an anatomical nature …” and delivered a whole speech critical of the idea.

In any case, his is a story of resilience, talent and rigour. In 1893 he published a book called “Nuevo concepto de la histología de los centros nerviosos” which was immediately translated in several languages and became the basis for a new way to look at the study of the nervous system.

The word “neuron” was coined around the same time by Wilhelm Walyeger after studying these new developments. In 1906 Ramón y Cajal shared the Nobel prize for Physiology & Medicine with Golgi himself (who, as we saw, still wasn’t convinced by his work …). After that, he became a national legend, but with his humble and servant-oriented personality he always kept a low profile, devoting his time to teaching and research and setting up organisations to help young Spanish researchers advance in their work and get international recognition. He really believed in science, he looks to me like a genuine passionate scientist who didn’t care for politics and fame.

I don’t think he is very well known to the general public, and that’s a shame given the importance of his discoveries, so I thought I’d write a few lines.

The artificial neuron

The neurobiology of the brain has inspired the idea to create “artificial” networks of “artificial” neurons that could function as mechanisms to learn patterns. Neurons transmit information by virtue of electrical and chemical signals that propagate through the cell and act at the interfaces, the synapses. In an artificial paradigm aimed at creating a modelled representation of a neuron, we can envisage units that emit an impulse (“fire”), hence passing information to neighbours, or stay quiet.

🚨 It is super important to stress though that artificial neurons and networks have never been designed to “imitate” the brain. As F Chollet writes in his book “Deep Learning with Python”,

“The term neural network is a reference to neurobiology, but although some of the central concepts in deep learning were developed in part by drawing inspiration from our understanding of the brain, deep-learning models are not models of the brain. There’s no evidence that the brain implements anything like the learning mechanisms used in modern deep-learning models. You may come across pop-science articles proclaiming that deep learning works like the brain or was modeled after the brain, but that isn’t the case.”

Biology worked as an inspiration, not as something to resemble.

You know I like to doodle to show concepts. In the following, rather than doodling on paper I’ve used a brilliant tool called Excalidraw, which allows you to create quick illustrations with a handmade feel.

A basic unit

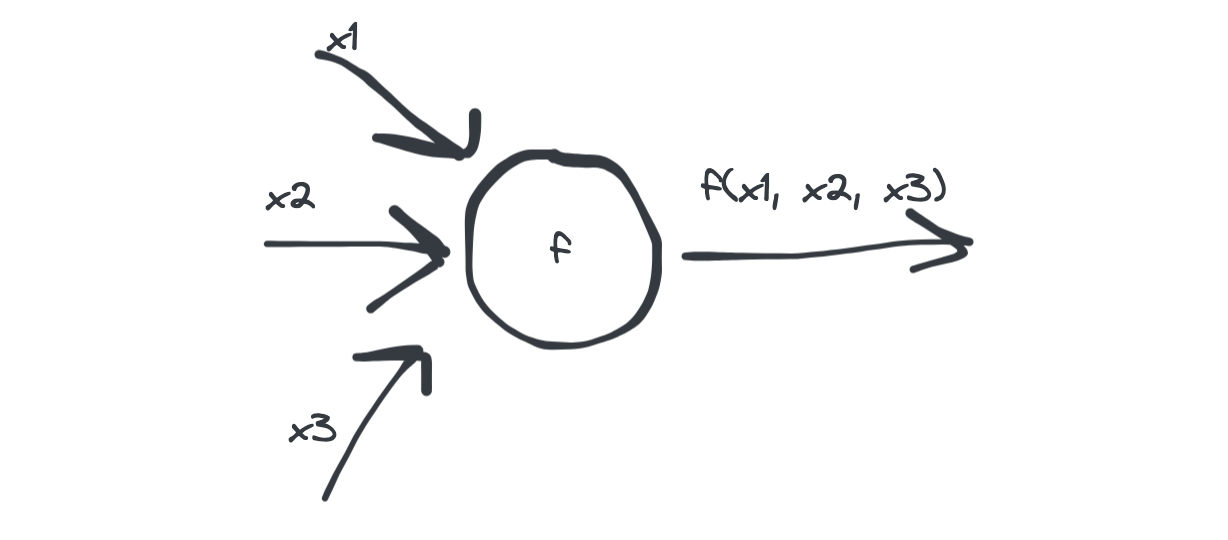

An artificial neuron can be thought of, in its bare bones, as a entity that takes several inputs, say \(n\) and call them \((x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n)\), and generates one output by applying a function \(f\) on them:

\(f\) is known as the activation function and it can vary depending on the type of neuron one is building - we will see a very simple version in the following section. Before getting passed to the activation function, inputs are added up, so effectively the output is given by \(f(x_1 + x_2 + \cdots + x_n)\).

The McCulloch-Pitts unit

In 1943 W MCCulloch and W Pitts (yep, it’s the prehistory of AI) developed a simple mathematical model for an artificial computing unit which used the idea illustrated above, but assumes that

- inputs are binary, meaning they can take only 1 or 0 as value

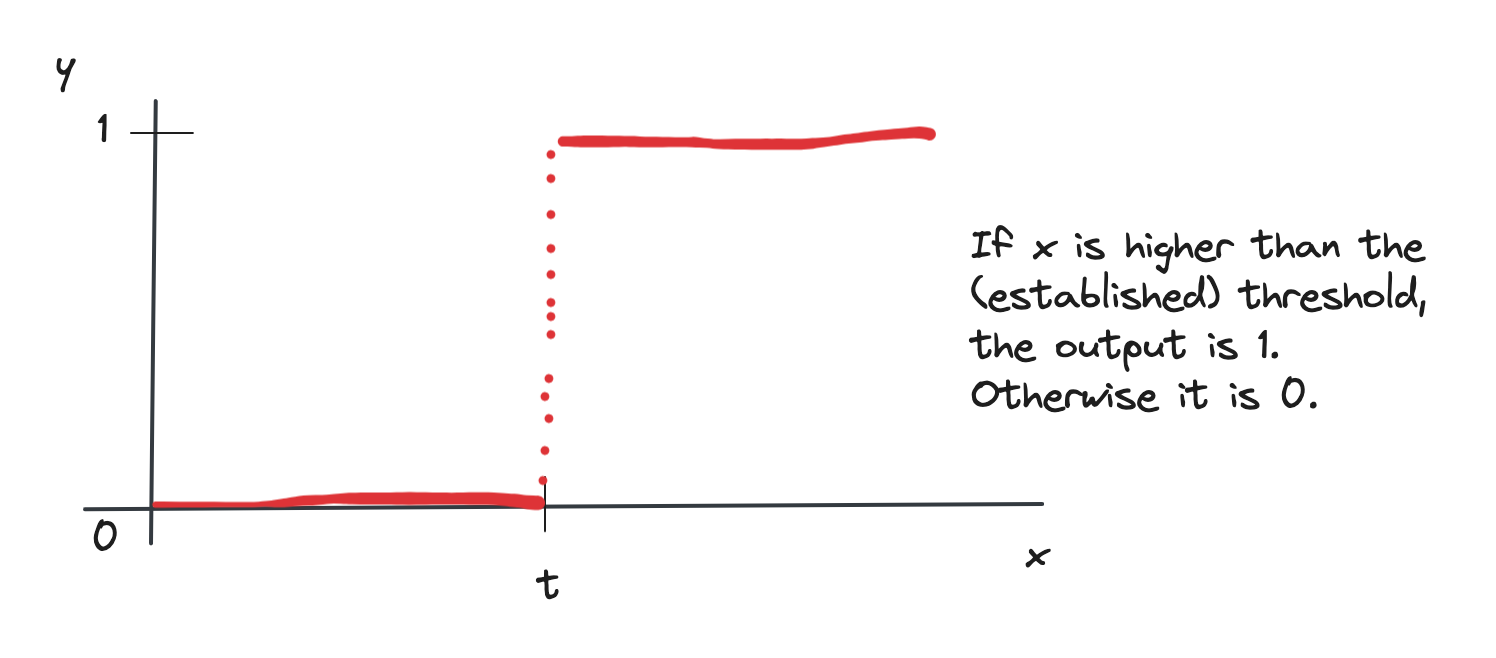

- the activation is a step function, based on a threshold \(t\): the unit fires only if the sum of inputs is greater or equal than \(t\)

- inputs can be excitatory (which means they pass through) or inhibitory (which means a 1 is inhibited, that is, doesn’t pass through). Inhibitory inputs are usually identified by a circle in the diagram

This is the step function:

which mathematically writes as

\[f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & x \geq t \\ 0 & x < t \end{cases}\]The McCulloch-Pitts unit was the basis of the simplest neural network built, the Perceptron.

This paradigm is really simplistic and not the one used today anymore, but it is nevertheless extremely educational to visually see how we can process simple functions, like logic ones. I have used Rojas’ book (see references) as the basis for this part.

In the following, we’ll use the standard convention whereby 1 means True and 0 means False.

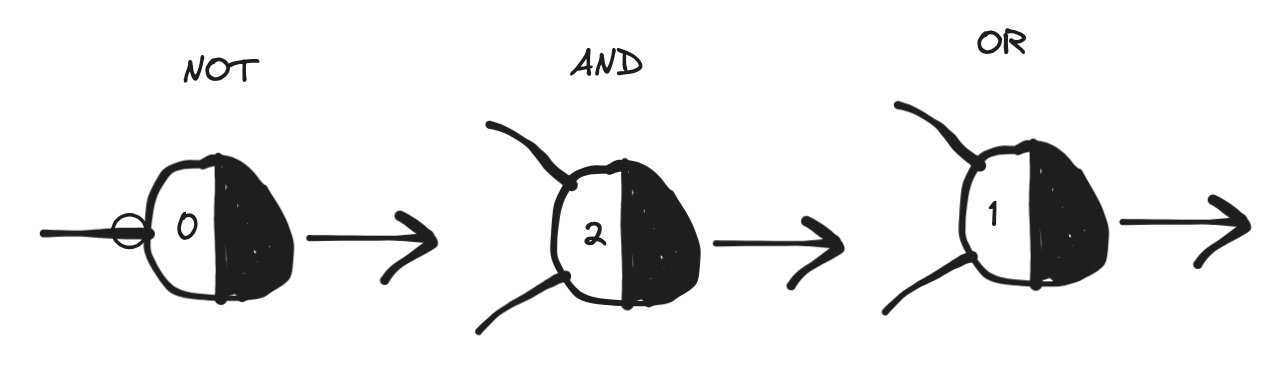

Let’s walk through the basic logical functions. When a function takes more than one input we will show the simplest case with just two, but the reasoning can be easily extended to a generic number of inputs. We will represent the McCulloch-Pitts computing unit/neuron as we did above, but we will split the circle into two halves where the second is black - this is to signify that the white part is the one receiving the inputs and the black part spits the output. Also, the threshold will be indicated on the white half. I’ve learned this convention from Rojas’ book which itself takes from Minsky’s work (see references).

Basic logical functions

We’ll look at the NOT, the AND and the OR.

The NOT

The NOT function works on a single input - it simply flips the value of what’s in input. In terms of a logical proposition, “I go to the gym” becomes “I don’t go to the gym” and vice versa. The truth table is:

| \(x\) | NOT output |

|---|---|

| 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 |

This can be easily encoded with an artificial unit by using an inhibitory input (note the circle on the edge) and a threshold of 0:

- when the input is 1, the inhibition doesn’t let it pass and the unit doesn’t fire, so we have a 0

- when the input is 0, the unit fires because it is greater or equal (equal in this case) than the threshold

The AND

The AND logical function (logical conjunction) with two inputs yields a True only if both are True. From the perspective of logical propositions, if I say “I go to the supermarket and I buy apples”, it means I do both things. If any of the propositions or both are false, the result is false. Truth table:

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | AND output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

This can be encoded as a unit whose threshold is 2 and with two inputs:

- when both inputs are 1, their sum is 2 which is why the step function outputs a 1

- when inputs are different their sum is one, which doesn’t pass the threshold and output is 0

- when both inputs are 0 their sum also doesn’t pass the threshold and output is 0

The OR

The OR (logical disjunction) with two inputs yields a True if any or both of the inputs are True, False otherwise.

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | OR output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

The OR can be encoded by a unit with a threshold of 1:

- when one of the inputs is 1, the output is 1 because the sum passes the threshold

- then both inputs are 1, the sum is 2 so it also passes the threshold

- when both inputs are 0 the threshold is not passed

About the XOR

Watch out: in regular language, usually, when we use an “or” to connect two propositions we actually mean the XOR operation (exclusive OR), which doesn’t yield a True if both are True (it admits only one of the two), like when in English you say “I’ll go to the gym or to the cinema”, better and more precisely phrased as “Either I’ll go to the gym or to the cinema”. I guess we’d enter a linguistic discussion here with this, which is out of scope.

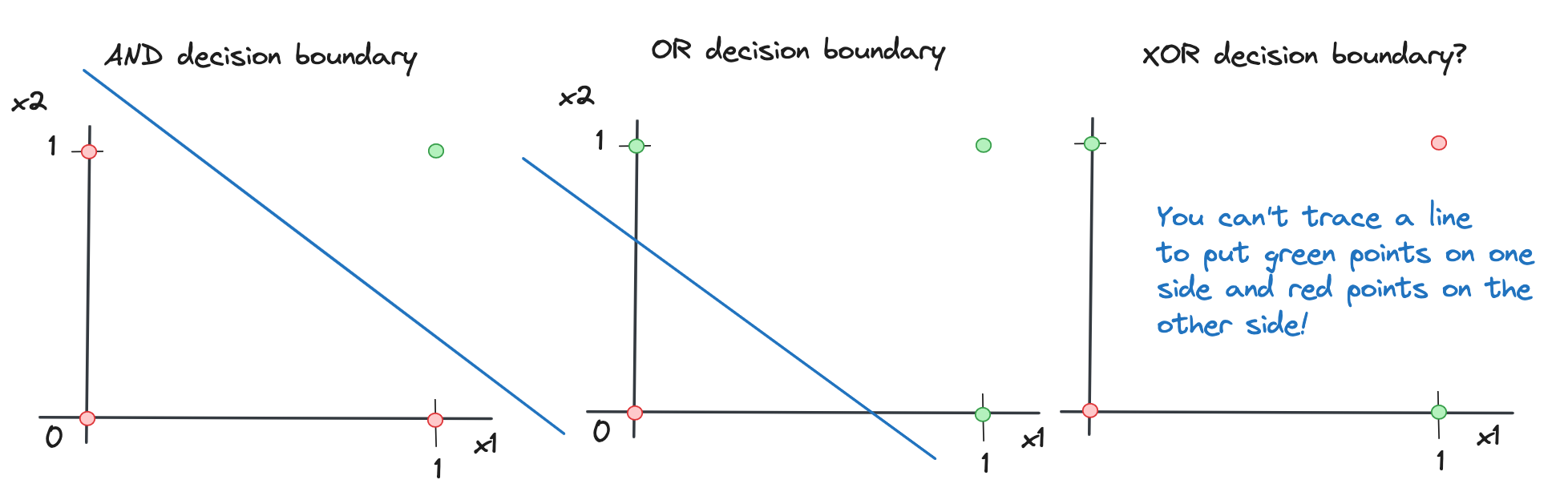

But an important note about the XOR function is that it cannot be encoded with a single computing unit! This is because the boundary between output values cannot be a line and our little McCulloch-Pitts unit is only capable of separating outputs linearly by value. Let’s see what we mean. The truth table of the XOR reads like this:

| \(x_1\) | \(x_2\) | XOR output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

If we look at the decision boundaries of the previous logic functions and this one, which are the divides between output values, we have this situation:

For the XOR to be encoded, a more complex structure is needed that adds non-linearity. I’ll probably expand on this point in another post at some point, but for now, I hope you enjoyed this and as always any feedback is appreciated! Read more on all this in the great references I refer to below.

References

- A quick history of the barber-surgeon

- H Scheuerlein, C Pape-Köhler, F Köckerling, Wilhelm Waldeyer—An Important Scientific Researcher of the 19th Century in the Context of His Memoirs and Major Monographies, Front Surg, 2021

Some good books

- R Rojas, Neural Networks, Springer, 1996

- M Nielsen, Neural Network and Deep Learning, 2019 (free)

- F Chollet, Deep Learning with Python, Manning, 2017

- M Minsky, Computation: finite and infinite machines, Prentice-Hall Intl., 1967

On Ramón y Cajal

- Google Arts & Culture has (at least) 2 online exhibits on the life and work of Ramon y Cajal (one, two)

- Santiago Ramón y Cajal, the Young Artist Who Grew Up to Invent Neuroscience, Scientific American - interesting article as it shows how the concoction of art and science is a common theme for scientists

- Beautiful Brain: The Stunning Drawings of Neuroscience Founding Father Santiago Ramón y Cajal, The Marginalian.