Entrepreneurship, social impact, and Olivetti

In Italy, Olivetti (the company) is a well-known case of a missed opportunity. I have always been intrigued by its (hi)story, both out a personal, albeit loose, connection, and because of a general fascination towards a tale of technological innovation coupled with social entrepreneurship. I cannot judge how peculiar this tale is in the global history of business, but I think it deserves knowing.

The company still exists (I didn’t know to be honest, I had assumed it went bust decades ago) but it is very different from what it used to be, and some say it could have been: after a few happy decades it fell into a trap of bad management and shortsighted decisions that killed its pioneering efforts and its soul for good. Born as a typewriter manufacturer in the early years of the 20th century, it had an interest for developing new technologies since its very start; during the 1950s and 1960s it was pretty ahead of its time within the area that would later come to be known as informatics, performing pioneering research in the development of early computers.

Olivetti’s appeal (to me, at least) isn’t solely due to its significance in the history of tech, however. Olivetti also constructed a functional microcosm of entrepreneurial results coupled with direct social impact on the community around it: that of its workers and, more at large, the people living in the area. Profits were reinvested into projects that improved people’s lives and employees were considered as individuals to nurture rather than mere labourers. Needless to say, these were quite radical concepts for the era.

My interest was recently reawaken by this new podcast by Italian newspaper “Il Sole 24 Ore”, which is the source of most of the information I report in this post. Also, some years ago the Italian public TV screened a show which (I think) was my first encounter with this story. I’ve been watching the show again these days, it’s quite romanticised but I still enjoyed it. Note that the loose connection I have with Olivetti rotates around the factory in Pozzuoli, which is near where I’m from in the South of Italy (see it on Google Maps). The area isn’t a developed one, for Western standards; Olivetti decided in 1953 to open up a factory there in front of the gulf of Naples (I’m not sure but I think it’s the only one the company, which was from the North of Italy, opened in the South) as part of its big plan of social entrepreneurship rooted in the territory. I was born in 1986, this factory had already been long closed when I was a kid, but I’ve heard the story many times via older relatives and friends. I think that this factory has remained closed for very many years until recently (in the last decade or so) when it has been taken over by the University of Naples and is now used partly as research centre and partly for teaching. Which is a great idea, in line with the original purpose. Plus, it looks great, take a peek at the photographs following the links above.

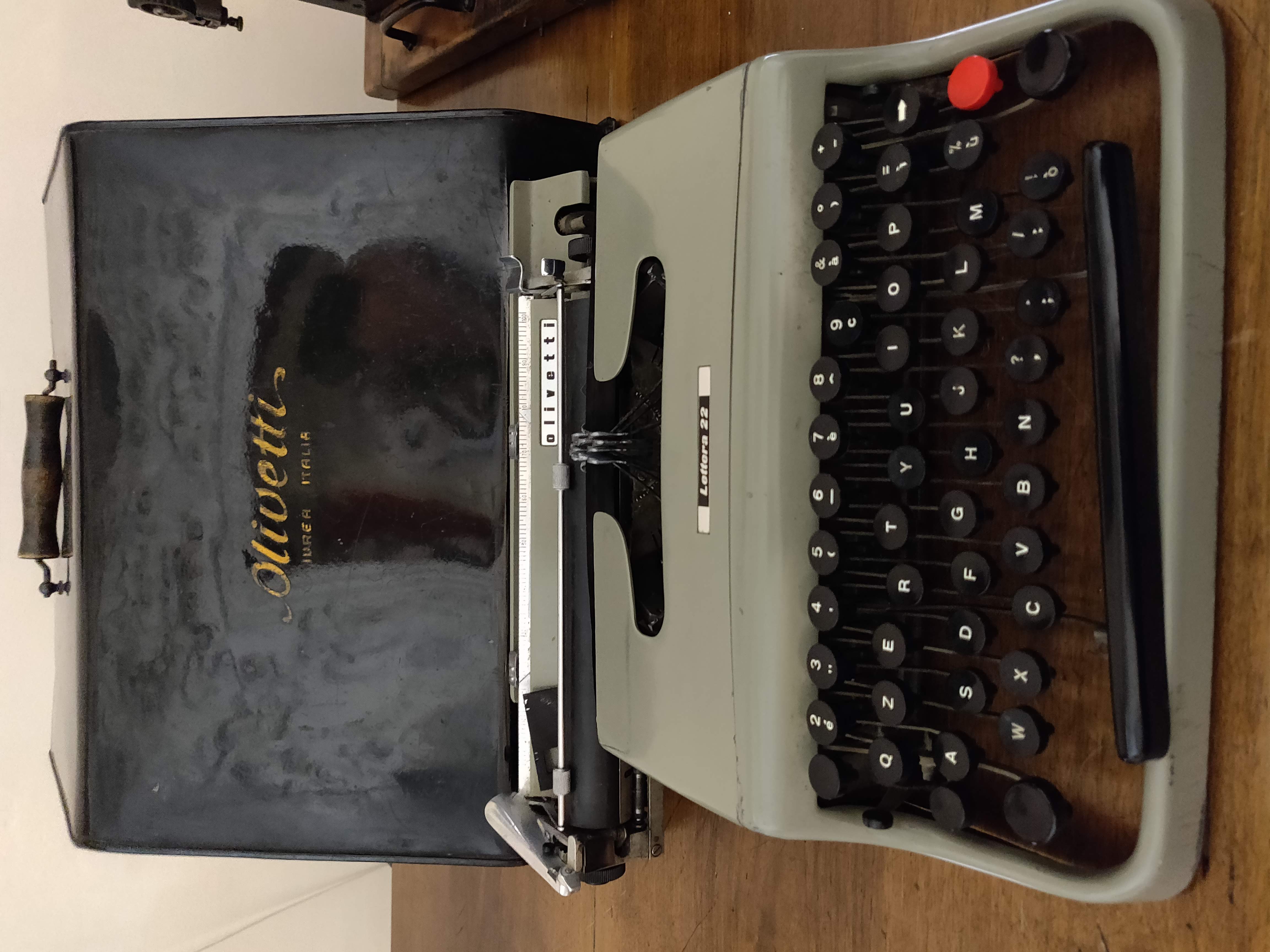

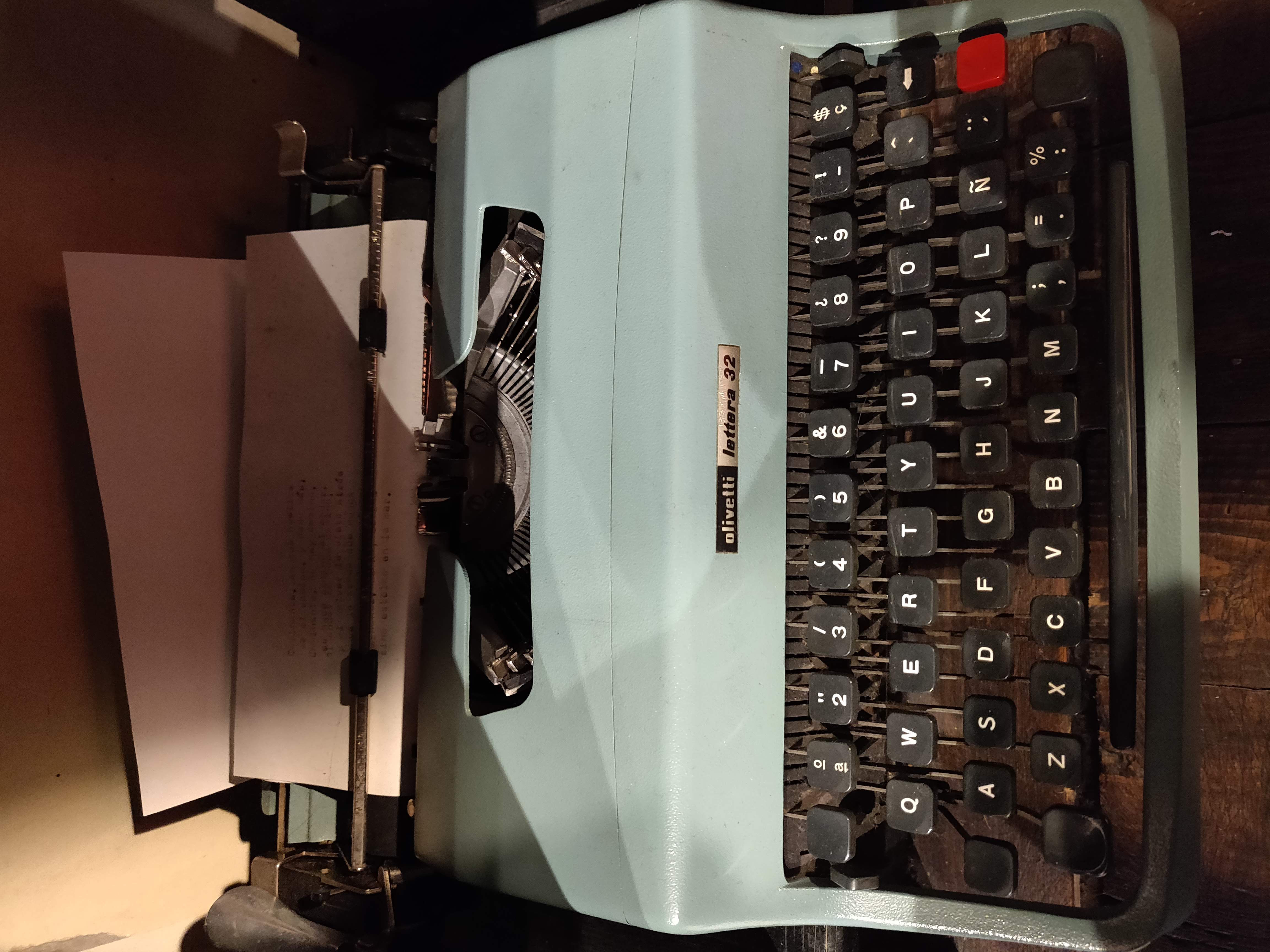

The photos in this blog are mine - the first two have been taken in the public library in Piazza Armerina, Sicily, which hosts a little museum too, and the third in the Typewronger bookshop in Edinburgh.

The story in a nutshell

The Olivetti company was founded in 1908 in Ivrea (near Turin) by Camillo Olivetti, to produce typewriters. C. Olivetti had an innovation mindset refined by trips in the English-speaking world, so his company was destined to be future-oriented even in its early days.

Adriano Olivetti (one of Camillo’s sons) inherited the business in 1938 and followed on his father’s footsteps, but with a much broader plan: a visionary and generous spirit, he wanted to establish a novel movement of social entrepreneurship aimed not solely at producing goods, but also at giving workers a better life, an education, quality services, while at the same time fostering research in technology and science. The new Olivetti becomes a volcano of innovative products: between 1945 and 1959 it creates a new product every 8 months. It performs research in the branch of what would be later called informatics and scouts out the best engineers and technicians around (including from abroad), establishing an electronics research branch and pushing for doing new things all the time.

The company’s research is pretty futuristic for the times, and very high quality.

A. Olivetti doesn’t believe in the canonical, old-fashioned production systems, where workers are stuffed together in small spaces, perform repeated actions, have no time to enjoy themselves. He equips factories with libraries, cinemas, outdoor areas with green spaces, he hires philosophers, actors, artists to provide cultural activities within the factories. The company also helps his employees buy houses, provides free transportation from and to work, guarantees 9 months of maternity leave and healthcare cover to people at a time where these things were not for granted. The salaries Olivetti pays are 50% higher than those of the competition for the same roles, working hours are reduced, Saturdays are free.

In 1958, Olivetti is a global company with 25000 employees and an important US branch. In 1959, it even acquired the historical American typewriter manufacturer Underwood. A Olivetti has big plans for the Italian society as a whole beyond his company, but not many follow him, in the government and amongst his fellow entrepreneurs too.

The end

In 1960, A. Olivetti suddenly dies. The company then starts undergoing continuous management changes, acquisitions and splits that eventually led it to where it is today: the original soul gets progressively lost. In 1964 the electronics department, with all the research division of the company, gets sold to General Electric, under the shortsighted idea that it is a waste of money and time, and from that point onwards all the production shifts back to mechanical items, an industry now outdated but that was foolishly considered safe by the new management. Here starts the sad decline.

However, even without management support (actually, with dissension) and not much funding, some engineers at Olivetti managed to produce the P101, an electronic calculator that Italians tend to call “the first personal computer in history”, however the claim is debated, both on whether it is truly to be considered a computer and on whether it had been the first of its kind. Either way, it was really a work of ingenuity and very inspirational. The P101 (the P stands for “programma”) gets displayed at an office products fair of in 1965 in New York City, generating immediate attention. After a few months, it is released on the market, selling for (just) $3200, and it goes down really well! Some models get even utilised at NASA for the Apollo missions.

Years later, the chief designer for P101, M Bellini, has declared that S. Jobs gave him a couple of calls trying to convince him to work for the then nascent Apple.

Today, all the material produced in those years, including photographs, advertising posters (Olivetti was also forward-thinking in the way it presented itself to the public), films and documents is preserved by the Archivio Storico Olivetti in Ivrea, which is open to the public for visits. Plus, there is a foundation which keeps promoting A. Olivetti’s ideas for a fair and innovative entrepreneurship rooted in the territory. Ivrea itself, the city where the company was born, in Piedmont, has become a UNESCO heritage site in 2018 for its significance as an industrial city with a social aspect.

Lessons for today?

I have been procrastinating the writing of this blog post for weeks now, because I felt I lacked a real message. Much has been written, podcasted, screened and documented about this story already (arguably not much in languages other than Italian though) and it is of course superfluous for someone like me, a regular citizen not linked to the story, to repeat it.

At the same time however, I spent time reflecting on the significance of this little portion of history and what it can possibly still mean today. I am just left with questions though.

Has Olivetti’s idea of business intertwined with social impact seen light in the decades after its conception? We’ve certainly come a long way, at least in “developed” countries, since the times of class-based privileges, but there is still much to do: are we on an upward trend that can only keep improving equality and wellbeing for everyone? If you read Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now”, it certainly seems so.

What is the purpose of doing business today, and has it changed since decades, or centuries, ago? Of course, there’s always been people who set out to start companies not only to create wealth for themselves but to impact positively on the general economy and generate innovation for everyone’s benefit, but has this gotten more prevalent in time? And if so, is it because of a general progress of our society that underpins everything, or is it something that characterises the world of business independently? Has the digital revolution fostered the idea of companies that serve all of humanity, or has it polarised us more, with the growth of a few tech giants whose services we all (literally) rely upon and a drive towards a monocultural approach towards doing business, that of the techbros of Silicon Valley? What would have someone like A. Olivetti thought of this?

And more philosophically, was Olivetti’s project a complete utopia, not really possible in any society, or was it just (much) ahead of its time like the company’s products themselves?

Read more and all references

- Olivetti, l’occasione perduta, podcast series, Il Sole 24 Ore (Italian)

- The Olivetti factory in Pozzuoli, Italian Ministry of Culture

- Olivetti Programma 101 Electronic Calculator, page on the Old Calculator Web Museum

- The Italian soul of Steve Jobs, National Museum of American History

- Mario Bellini, l’italiano che disegnò il primo PC: “a Steve Jobs dissi due volte no”, Corriere della Sera, 2017 (Italian)

- Archivio Storico Olivetti

- Fondazione Adriano Olivetti

- Ivrea, industrial city of the 20th century

- S Pinker’s “Enlightenment Now” on Goodreads