Delightful public talks

There are several types of public talks. There are exams you do at university, when you talk in front of a dual audience (the professor(s) and the fellow student auditors, if present); lectures (whose purpose is to actually teach things); academic conferences (where you present the findings of your research to a monolithic audience formed of people working in the same field); non-academic summits (where you talk about interesting things you did at work and share what you learned to the benefit of colleagues in other companies); videos on Youtube (where you can fascinate people with science, for instance, among other things); political speeches and press conferences; and a full plethora of other examples. What changes is the purpose of the talk and the audience. Obviously different audiences and scenarios require different sorts of structure and organisation of the talk.

I will be here referring to public talks in the sense of those conveying information with non-promotional purposes (conference-like ones and lectures, so to say).

But what makes a good talk good?

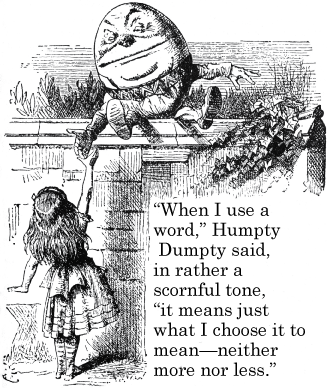

The views expressed here are just the result of my collecting ideas after having accumulated a relatively conspicuous experience on both sides: that of the speaker and that of a member of an audience. I have given bad talks, I have given good talks, I have listened to useless and boring talks and I have been learning a lot from delightful talks the impressions of which I still remember now. It is very well known (and actually a little commonplace) that a good talk is one that tells a story. A speaker capable of keeping her audience engaged will be conducing the public by hand in a stream of logically linked small steps from a starting question to the argument. This type of speaker can build a tale along the way, hence keeping people curious for the next chapter. Eventually, she will expect questions challenging her arguments which might force her to consider a new point of view: this is the ideal situation as both the speaker and the audience would have learned something, creating a win-win condition. It is also repeated everywhere that not receiving questions at the end is the ugly symptom of having bored the audience or not having made the message go through. I do believe that these two are good points. A talk is meant to convey information, in the form of a statement or an argument, but it should be food for thought for the audience, rather than a sterile presentation of concepts. A talk should not confuse people via badly-developed chains of thought. If people at the end look away when you ask “are there any questions?”, if they yawn or start furtively leaving the room, you have failed. Either your reasoning was bewildering and poorly carried out or there was no substance at all in what you presented, nothing worth of discussion. I would like to comment a little on what I learned it means, for me at least, that a talk is enjoyable, both for the one who talks and for the ones who listen.

The title

The title should be relevant and convey, in a nutshell, what the presentation will be about. I have assisted to examples of titles not matching content beyond the level of a vague relationship amongst buzzwords. Needless to say, this is unlinkely to happen in the case of scientific presentations, but I find it disturbingly common in more general-purpose ones. A good title is at the same time informative about the content without being too detailed, and a reader will have to be able to tell what is in there before deciding whether to go and potentially invite other people. If, for instance, you will present something about how Vincent Van Gogh helped shaping the post-Impressionist movement and eventually led the way to Expressionism, you want to mention him in the title, but what you don’t want to specify there is that he led a difficult life which might have contributed to his sense of expression. Don’t be over-precise, give people a sense of what is going to be there in your content without going too far. Whet their appetite, but do not deceive them in thinking they will be listening to something you do not have.

The length

Nobody wants to bore people, I suppose. Usually talks may range from a 20-minutes slot to maybe longer, 50/60 minutes sessions. There is no golden rule for the optimal length but because we are all humans and have a limited attention span, potentially dependent on our experience (I bet my attention resists less now than when I was a student years ago and was able to crunch full long sessions on Quantum Mechanics with no problems), a speaker needs to have this clear. Introduce the topic in just as many details as needed to follow the main argument, then go straight to the point and finally conclude. Of course, there are also very short talk of 5 minutes or so, usually at those events where many people pitch their idea in a quick shot. Here you would have to be skilful in managing the time well to both shoot directly to the point and ignore all the details and technicalities about it.

The format of the slides

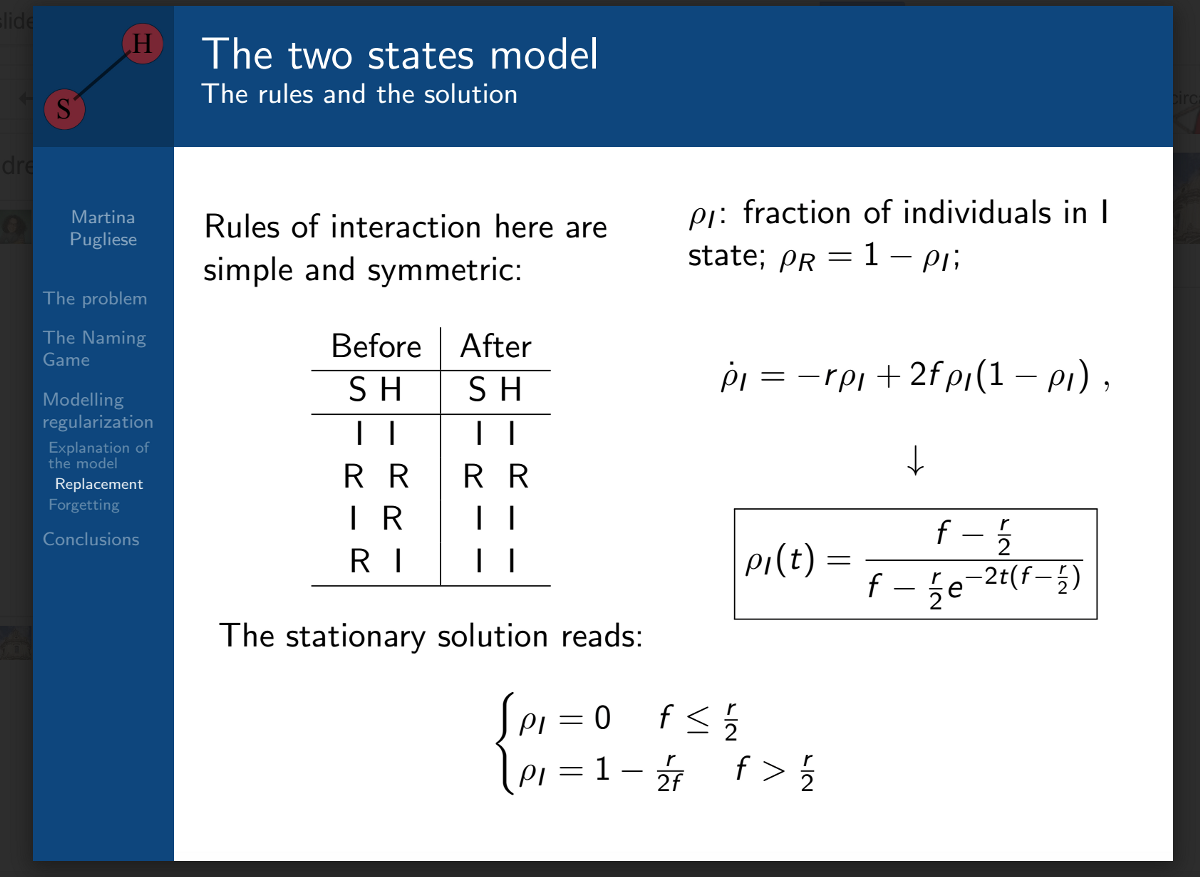

There are several tools around. I personally always used Beamer (LateX) when in academia and I would continue to for hardcore scientific presentations, where fanciness has to be sacrificed for clarity and substance. Beamer is ideal for writing mathematics and also is easily customisable to always show the outline and the “where you are” by highlighting the structure level.

In the figure, a typical Beamer slide: ideal for scientific presentations.

For non-academic talks, I find Keynote to be the best tool: it’s interactive via its drag-and-drop/click mechanism, it can be infinitely customised and saves you a lot of time. I have tried and also used Prezi more than once but I am not a great supporter of standalone fanciness, I believe you should be making your slides fun and intriguing yourself through the content rather than relying on tools. Prezi was very interesting when it first appeared as a new product but now that I got used to it I don’t get fascinated by its features any more.

The content and the structure

Unfortunately this is not always the case: it is not that unfrequent to encounter self-promoting talks or speeches aimed at selling products, where a product can be simply your Twitter or Medium account really. In the liquid stream of information we occupy several people make a business out of promoting themselves and get paid by your clicks on their content. Nothing particularly new here, and exploiting the possibility to give a talk to publicise themselves is the equivalent of placing an advertisement for something new on an old medium. I am not criticising these types of talks, but I do believe that if you organise an event and make it understood that you are going to talk about something and then start talking about yourself and promote your products, you are being dishonest to the people who came listening to you. Be clear from the start instead.

A good speaker calibrates words and visuals to convey information. The tone and register of the speech have to be tweaked to adapt to the specific audience and the type of purpose. Usually raising a laugh in the audience is considered enjoyable, if not expected, but don’t try to be too “funny”, it would be childish. I once failed miserably (and it still hurts!) at trying to be amusing and making the audience grasp the fun behind what I was saying. Nobody laughed, was a little embarrassing actually. Some level of interaction with the public is often well met, people like answering polling questions which help your argument and keep them awake. TED talks are so powerful because of the intensity of their content, certaily not because the speakers try to convince you of anything. It is their outstanding work which speaks for them. When you finish speaking and answering questions, try thinking about whether you think you succeeded in sharing some bits of knowledge, or experience, with the people who were there listening to you. Do you think they came home feeling they learned something? Were their pre-concepts challenged? Would they say their time was well-invested? Then, ask yourself if you learned something new: by putting your thoughts into a shareable form you give them the possibility to be criticised, and this if often (when performed in a respectful way) an immense source of education. Someone wise (apparently Mr J. Joubert) said that teaching is learning twice.