Do we know our cooking fats and oils?

There’s several types of fats used for culinary purposes, the most common of which are probably sunflower oil, olive oil and butter (at least in the West). But there’s more, though some of the most exotic ones are at most used sparingly as salad dressings.

I guess it’s common knowledge that fats are of different categories having different impacts on human health. Without digging too much into details I’m now knowledgeable about, the WHO recommends a scarce use of saturated fats in the diet (less than 10% of the total energy intake) and a move towards higher use of unsaturated ones, which are mostly extracted from vegetable sources.

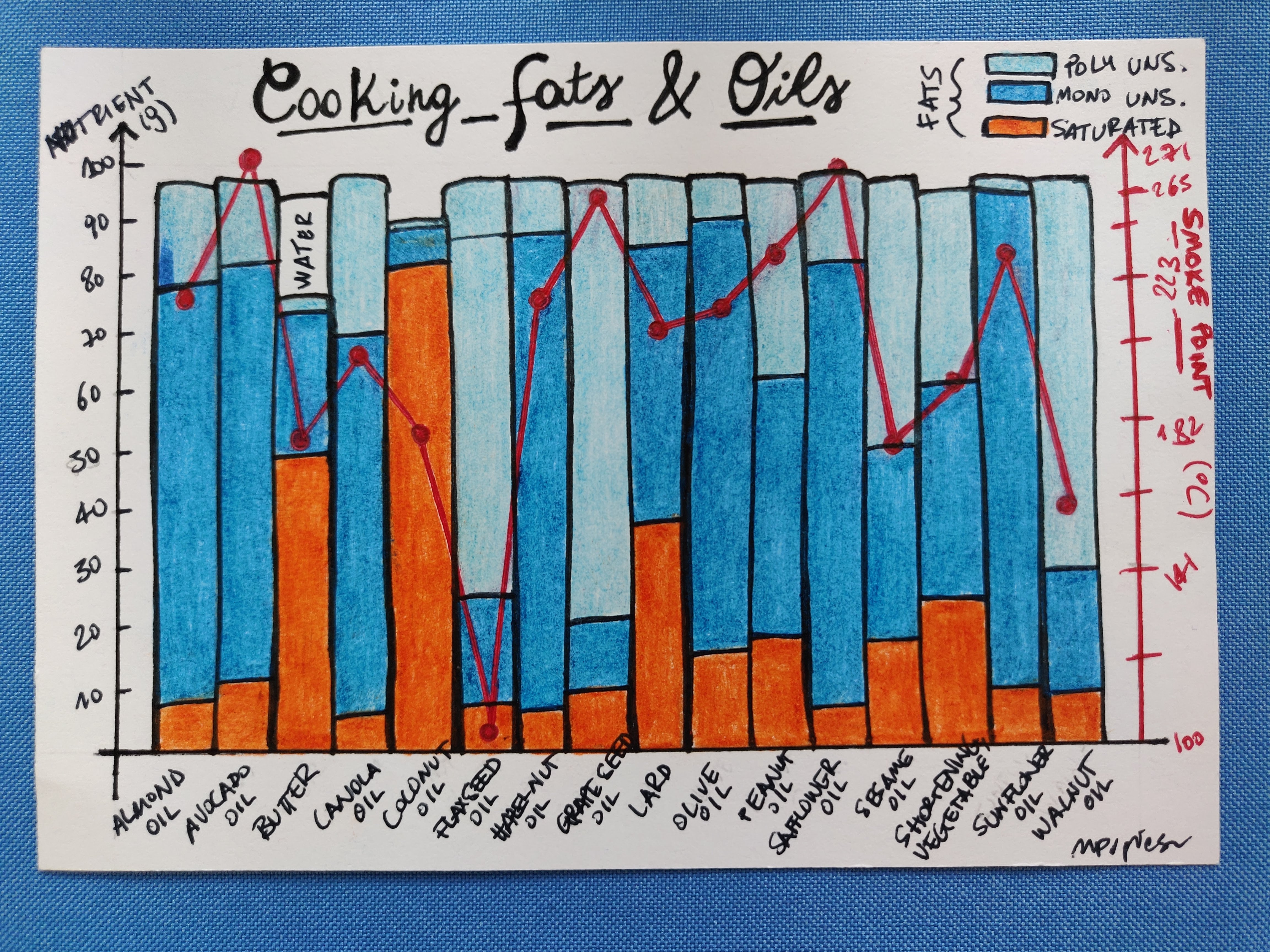

I’ve been looking at some of the fats and oils used in cooking for which I could find reliable data, and here they are:

- almond oil, derived from pressed almonds

- avocado oil, derived from, well, avocados (not the seeds, the actual fruit)

- butter, which comes from animal milk, usually cow’s one

- canola oil, derived from rapeseed (I’m not exactly sure about the difference with rapeseed oil)

- coconut oil, which comes from the whole (meat and milk) coconut fruit - it is often used in vegan foods as a replacement for what would be butter and, as you see from the chart, it’s not very healthy

- flaxseed (or linseed) oil, derived from seeds of the flax (a plant) - this really isn’t much used for food

- hazelnut oil, derived from pressed hazelnuts, likely mostly used as special dressing

- grape seed oil, derived from pressed grape seeds

- lard, derived from pig’s fat tissue

- olive oil (of which there’s multiple varieties, though I’m sure the same applies to the rest, it’s just that we know and appreciate olive oil a lot), derived from pressed olives

- peanut oil, derived from pressed peanuts

- safflower oil, derived from the seeds of the safflower

- sesame oil, derived from sesame seeds

- vegetable shortening, which is a type of shortening, or fat that appears solid at room temperature, and is made by hydrogenating a vegetable oil (margarine follows a similar process), the result is pretty unhealthy

- sunflower oil, derived from the seeds of the sunflower (and I believe it’s the most common choice for frying)

- walnut oil, derived from pressed walnuts

In the graph, I’ve plotted the fat content for 100 grams of product, split into saturated, monounsaturated and polyunsaturated - use the left y-axis for the scale and numbers. On the right y-axis and as a red line in the graph, you see the smoke point for these products, which is the temperature (here in Celsius) at which the oil/fat starts to smoke because it burns. What you want for cooking is a high smoke point, because past this temperature the product will release harmful chemicals.

For more about the smoke points of fats and oils, Serious Eats has a nice overview, which also reports data.

So what do we learn?

First of all, most of the fats in the graph are nearly 100% fat - the exception is butter which also contains a non-insignificant amount of water.

Then, you see that animal fats, coconut oil and shortening are high (some very high!) in saturated fats - these are generally things that we should use with frugality in the diet. I just had an idea for a follow-up data card: the butter intake one would have via the consumption of certain - industrial - foods, as butter is very widespread in processed food (and also some cuisines)!

Coconut oil is high in saturated fats, and because it’s widely used in processed vegan alternatives to meat and dairy, it is important to know what effects this may have - vegan food isn’t necessarily healthy. Some studies are linked in the references.

The oil with the highest smoke point is the avocado one, ~271 °C. I’ve tried it, strong flavour but quite nice.

The data I’ve used

For the nutritional content, I’ve used the USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture) database, reachable here. You can download datasets and they contain lots of info, including the nutritional content of a bunch of foods they categorize. I’ve used the JSON files from the legacy datasets (because they seemed to contain more info than the new ones).

For smoke points, I wanted a published source and I found the book “Culinary Nutrition - the Science and Practice of Healthy Cooking”, for which the page previews freely available on Google Books contained a table of smoke points - I’ve selected the fats/oils reported in there as my set. Disappointingly, palm oil wasn’t there, so I don’t have it either.

If you’re interested in the actual numbers, I’ve compiled them in this sheet.

Stuff to bring-along

This is where I recommend some things related to the topic.

An app

Disclaimer: I am not an influencer and nobody is paying me to recommend this app, I just do it as I think it’s great and works wonders.

The app is called “Cookbook - recipe Manager” (link is for Google Play but I’m sure it exists for iOS too) and is one of the few apps that convinced me to purchase the paid version.

It lets you import recipes from links but also from photos - it parses webpage content/applies OCR to extract structured elements, and results are normally pretty good, even in languages other than English. I use it a lot to store recipes both in English and Italian and it’s much better than the archaic way I was using earlier which was a spreadsheet and/or a scrapbook of pics and paper snippets.

Plus, it lets you search for recipes in your collection by name, tags, keywords or by whether they contain chosen ingredients, which is awesome! You can also plan your meals, but it’s a feature I personally don’t use much, however it’s useful to quickly get the shopping list from what you want to cook (it does that). All in all a really good app.

A cookery book

Who doesn’t like cookery books, with all the awesome pictures and that calm sense of zen they exude? I do, but I have 0 space in my flat so I buy them super-rarely. However, this one’s quite thin and light and what I love about it is that it gives you “scientific” tips at each recipe. It’s “Easy culinary science” by J Gavin, a culinary scientist. I just bought it and I still have to cook anything from it, but it looks good.

For the Italians: yes I am a fan of Bressanini’s scientific cookery books too!

An academic (but fun) course

Some time ago I had found this course on YouTube, from the Harvard University: Science & Cooking, I’m linking a playlist which contains the whole lecture series from several years. There’s many gems in there, if you like learning more about what I think is a fascinating topic: the science of how things get cooked.

References

- The WHO guidelines on a healthy diet

- J B Marcus, Culinary Nutrition - the Science and Practice of Healthy Cooking, Elsevier 2013

- J Gavin, Easy Culinary Science for Better Cooking, Page Street Publishing 2018

- Science and Cooking, lecture series from Harvard University, freely available on YouTube

- CookBook - Recipe Manager, great app, recommended

- Serious Eats on the smoke points of fats/oils

- Food search (and data downloads) from the U.S. Department of Agriculture

- M Pointke, E Pawelzik, Plant-Based Alternative Products: Are They Healthy Alternatives? Micro- and Macronutrients and Nutritional Scoring, Nutrients 14(3), 2022

- W J Craig et al., Nutritional Profiles of Non-Dairy Plant-Based Cheese Alternatives, Nutrients 14(6), 2022

Oh, I have a newsletter (see link in navigation above), powered by Buttondown, if you want to get things like this and more in your inbox you can subscribe from here, entering your email. It’s free.